2. Sequences of action

A helpful way for us to understand conversation, is to think of turns at talk as social actions. Each action responds to a prior action and prompts a relevant next action.

Rather than thinking of turns as saying something, we can think of turns as doing something.

Re-framing our understanding of talk-in-interaction as a series of actions allows us to see how speakers achieve these actions using a range of resources, such as word choice, prosody, emphasis (volume, or exaggerated pitch change), audible in breaths and out breaths, eye gaze direction, bodily orientation, facial expressions, gesture, and so on. Understanding talk-in-interaction as a series of contingent actions allows us to consider the most relevant next action. This sequential organisation of talk not only allows us to make sense of one another, it provides the vehicle for therapeutic interaction.

In the previous module, we thought about the fact that in conversation, one turn occurs after another. In this module, we will explore the fact that each next turn is tied to the previous turn in some way: (1) often as a pair; (2) with a preference for a particular type of next action; (3) with actions building on the prior talk in longer sequences. Let’s start with the most basic type of sequence, the adjacency pair.

2.1 Adjacency pairs

The most basic, minimal sequence in conversation is an ‘adjacency pair’ (Schegloff & Sacks, 1973) – that is, two turns produced by different speakers which necessarily occur together. The concept of adjacency captures the principle of nextness. In other words, the turns are apposite, proximal or right next to each other. For example, a question, as a first pair part, sets up an expectation of an answer as a second pair part. It functions as a pair, because a question must have an answer; if no answer is provided, it is noticeably absent.

Here is an example of the interactional obligation of an adjacency pairs in action: How difficult is it to leave a question without an accompanying answer?

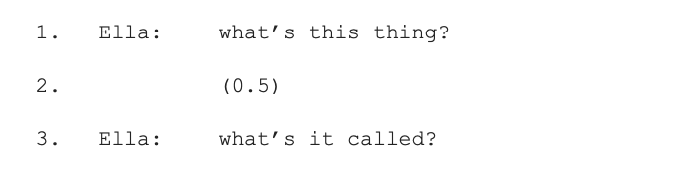

Even very young children know that an answer should follow a question. Here is Ella (aged two years and 8 months) asking her father a question (see Forrester, 2017, p.266):

Ella’s father does not provide a response immediately, so after only a 0.5 second delay, Ella asks another question. By pursuing a response, this toddler makes relevant her father’s failure to respond to her question. (Side note: This is one of the reasons why toddlers ask so many questions – it’s a great way to get an adult to talk to you because responding is conversationally ‘compulsory’.)

So pervasive is this sequential organisation of pairs in talk, that failure to provide an answer is oriented to as noticeably absent. This accountability is relevant for therapists, as the interactional imperative to provide a response, means that clients are (conversationally) obliged to respond in some relevant way. If an answer cannot be provided, some account needs to be given for this failure to respond.

“By the conditional relevance of one item on another we mean: given the first, the second is expectable; upon its occurrence it can be seen to be a second item to the first; upon its non-occurrence it can be seen to be officially absent – all this provided by the occurrence of the first item.”

Question-answer sequences are only one type of adjacency pair. Can you identify other common pairs of turns in conversation?

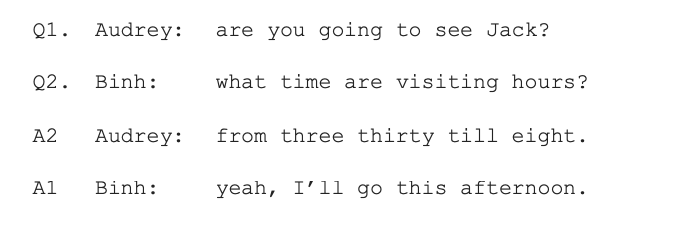

Our orientation to this norm of adjacency pairs is so strong, that we treat any next action as relevant in some way. Consider the following example from a telephone conversation between two women about visiting a mutual friend in hospital:

Audrey does not treat Binh’s question as a non-response to her own question. The fact that she answers (in A2) by providing the visiting hours demonstrates that she hears Binh’s question as relevant to her own. This is an insertion sequence, something to resolve before the relevant second pair part (ie answer to the first question) can be provided.

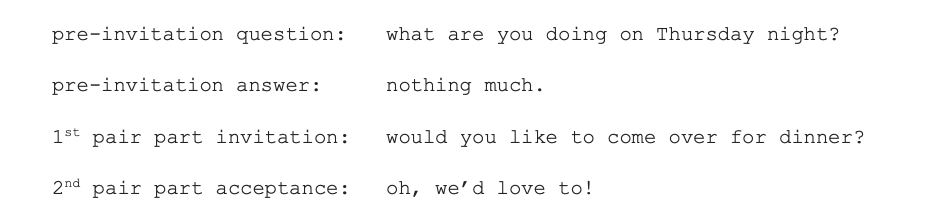

We universally orient to the norm that a question must have an answer, a request must an acquiescence or refusal, an invitation an acceptance or declination, and so on. The base adjacency pair may have any number of insertion sequences, (here’s a very long example!) or pre-sequences, or post-sequences. An example:

This type of pre-sequence is very common before invitations: we see if it is likely to be accepted before issuing the invitation.

Likeliness – or being able to anticipate what sort of second pair part – is managed by the principle of preference organisation in conversation.

2.2 Preference organisation

We have seen that one turn occurs after another, one turn at a time, and that each turn leads to a relevant next action. But not all relevant next actions are created equal.

In the video below, Professor Liz Stokoe shows us how telephone call openings typically progress. Then she’ll play a recording of a call between boyfriend/girlfriend Gordon and Dana where things don’t go so well.

Openings of telephone conversations are done in very predictable ways.

We can hear that Dana’s responses are marked as not-the-usual type of turns in an opening of a phone call. She does not do the preferred next action, which is to provide an immediate and reciprocal next action.

The fact that second pair parts can be either preferred or dispreferred next actions allow us to see where things can go awry.

Note, this concept of preference organisation refers to a linguistic rather than psychological principle. Not the wishes of the speaker, but what the first pair part sets up as the preferred next action.

A next action is structurally preferred (not what the speakers ‘want’ or ‘prefer’) because it is the most straightforward next action, the relevant action that is most easily done. For example, invitations are designed for acceptance to done easily in the next turn, but declining an invitation takes more (interactional) work.

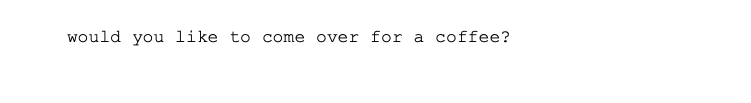

Consider the first pair part on an invitation:

How would acceptance be done? (i.e. the preferred next action) What if you couldn’t make it (or didn’t want to) - how would you refuse the invitation? (i.e. the dispreferred next action)

A preferred response would look something like:

Declining, on the other hand, would take a bit more work.

(The example above from Anita Pomerantz, was published in 1984, before mobile phones! The examples used here and below appear in Pomerantz & Heritage, 2012).

The key point is that preferred actions are always done immediately in short, direct turns. Dispreferred second pair parts, however, are delayed – by pauses or hedges such as well, uhm – and accompanied by an account for why the preferred action is not done.

In other words, we don’t hear this as a response to an invitation:

… even if you don’t want to go over for a cup of coffee.

Preference organisation makes conversation spectacularly efficient; the preference for progressivity in conversation means that the whole system is set up to be seamless as possible. In other words, preferred actions are more easily done.

These distinct turn shapes - immediate, short and direct (= preferred) or delayed, mitigated and providing some sort of justification (= dispreffered) mean that we can anticipate what will be done in the next turn.

For example:

The pause of two seconds after the speaker’s request is more than long enough to know that the answer will be a ‘no’, so the speaker moves to answer the pre-request herself.

Delay indicates that a dispreferred action is coming next.

Preference organisation is fascinating, predictable phenomenon. The reason these turn shapes are of interest to your professional practice, is that features of preference indicate how a client perceives a prior suggestion. For now, we simply note that these turn shapes are predictable and ubiquitous, and we’ll return to the relevance of preference organisation to therapy talk in Module 4.

2.3 Sequences of interaction

Adjacency pairs are simply a building block, and interaction is made up of a series of relevant next actions, building to conversation as a whole. Pairs of turns at talk are not produced in isolation, but instead are the base for building extended sequences.

Each turn at talk, then, responds not only to the immediately prior turn, but also on the turns before that. Conversation is cumulative.

This pervasively robust system of sequences of actions in conversation is notable for psychologists, because therapy – even though it may have distinct and different goals to everyday conversations – draws on the same architecture or set of rules. The imperative to answer questions persists, so it will become important to consider how, for example, clients manage to resist providing the obligatory second pair part.

Rather than think about interactional practices in isolation, sequential analysis of talk allows us to see how the therapist and client continually revise and re-frame their talk in light of what the other has just said.

“The construction of client experience during therapy is best viewed as a co-construction, which involves the negotiation of meaning between the therapist and the client. From this perspective, the therapist does not passively take in a client’s construal of experience. Instead, a therapist’s utterance is, in the classic conversation analytic sense, context shaped and context renewing (Heritage, 1984): a therapist’s turn at talk is shaped by a client’s previous turn and consequently shapes what clients will or can say next.”

The sequential organisation of talk-in-interaction is of particular interest and use to psychologists, because displays of understanding are made in each subsequent turn at talk. These displays show how the client is interpreting questions or comments made in therapy and reveals new perspectives or understanding to the client in what the therapist says next. We can document the process of therapy in the design and delivery of each subsequent turn.

The therapist can check for understanding and expand, confirm or revise in the very next turn. All this takes place almost instantaneously and seemingly effortlessly.

Here’s a very obvious example where there has been some (objective) misunderstanding during a Cognitive Behavioural Therapy session. (The video appears as an introduction to the training videos available at psychotherapy.net

This same mechanism for addressing misunderstanding, misperception or misalignment is used in navigating subjectivity in therapy.

When we notice things have gone off course, or some misunderstanding has taken place, we address this within the sequence of interaction itself. In fact, the ‘one turn at a time, one turn after another’ organisation of talk gives us an in-built mechanism for fixing misunderstanding. Conversation analysts call this fixing ‘repair’ which we look at in the next module.

Summary

In this module we have learnt that:

(1) adjacency pairs are the basic building block of series of actions in conversation;

(2) the preference organisation that operates in conversation enables the efficiency and progressivity of talk (i.e. for the conversation to continue as effortlessly as possible); and

(3) each turn builds on the prior turn(s) in longer sequences of interaction.

If we think of turns at talk as achieving some sort of social action, each turn prompts a relevant next action. We’ve seen that the relevance is governed by the type of prior turn and that preference is sets up an expectation – linguistically – of what should happen next. It is this very nextness of turns at talk in sequences of interaction that allows us to monitor how we have been understood.

Thinking about the content you’ve worked through in this section of the course, respond to the following reflection:

How can analysis of the sequential organisation of therapy talk be useful to psychologists?

You can return to the course homepage here, or continue by clicking on ‘Repair’ below right.