3. Repair

The fact that we interact one turn at a time, one turn after another provides us with a mechanism – built into the sequential organisation of talk – to check our progress with other speakers.

Rather than constantly having to explicitly seek confirmation of understanding (“did you understand that I meant ‘x’?), we can see, in the very next turn – by how they respond – what others make of what we said.

Essentially, in conversation there is a…

“next-turn proof procedure: we can see in the recipient’s response just how s/he understood the prior turn”

The nextness of each turn at talk allows for a display of understanding. In every turn the speaker has the opportunity to revise their talk, and the hearer can flag any trouble source (check for meaning, mishearing etc.) in the very next turn.

If there is a troublesource, any sort of problem, we can address this in the very next turn.

In conversation analysis, we call this fixing of troublesources repair.

In the next video, Dr Emily Hofsetter, Research Fellow at Linköping University, explains the fundamentals of repair in interaction.

3.1 Self-repair

This ‘human language fixing device’ allows us to monitor intersubjectivity and look out for misunderstanding – and moderate our own talk – as we go.

Let’s return to a few of the key points made in the video.

As Dr Hofsetter noted, repair is ubiquitous, and self-repair – where speakers fix their own talk – is so commonplace, we rarely notice it happening.

Often, self-repair is simply evidence of the inordinate speed with which we retrieve and produce words in our speech. In the following example (all transcript excerpts in this section appear in Kitzinger, 2013), the speaker intended to say ‘smaller’, a claim we can make on the basis of the evidence provided in the production of the turn:

These revisions-as-you-go are frequent and unproblematic as they barely interrupt the flow of talk:

Sometimes, self-repair expands the noun phrase (i.e. provides a little more information):

These short expansions serve to qualify the object of the speaker’s turn:

Evidence from everyday conversations also shows us that turns are recipient-designed. In other words, the speaker takes into account, what their audience might reasonably know. In the next example, the speaker clarifies who the ‘we’ refers to:

Speakers are constantly monitoring their own talk to consider what common knowledge they and their audience might know (i.e.‘theory of mind’ or knowing what another person might know). In the next example we see that the recipient (Norman) knows that the speaker (Ilena) is a grandmother, but not the name of the granddaughter:

Other revisions that speakers make in self-repair include upgrades to assessments:

And these upgrades can take any form:

From your experience and training in psychotherapy, you will have a range of insights into how a client’s revision of their own talk reveals intention, attitudes, misapprehension, or the subconscious.

Even those of us without your professional expertise can make inferences about what the speaker meant to say when they revise their own talk.

In the extract below, what does the self-repair show us about what Mia Freedman thinks of her audience?

The self-repair of “updates” (line 3) in place of “changes” re-specifies the type of changes Mia is advocating business owners make in their business. This is a typical sort of editing-as-we-go, using self-repair to make revisions that better capture what we are trying to say. We can see that “updates” clarifies making “changes” that improve the currency of the content.

The other self-repair in this extract does not make that sort of clarification. Mia repairs ‘imperceptible changes’ to ‘small changes’. The substitution is less specific. We don’t usually use self-repair in this way. Unless we think our audience doesn’t understand the word “imperceptible”.

Self-repair reveals all sorts of things about the speaker’s stance. If you’re interested, here’s data that show how racism might be on display, in examples of self-repair collected and analysed by Burford-Rice and Augoustinos (2018).

How (and why) speakers do self-repair is endlessly fascinating. In interactional terms, however, we are perhaps even more interested in how we might query another person’s talk.

3.2 Other-initiated repair

If there’s a problem, and the speaker doesn’t fix it themselves within their own turn, the recipient can flag that there’s an issue. The problem can be one of mishearing, misunderstanding or correcting the speaker.

Other-initiated repair, where the recipient flags a problem, is commonly done using what Drew (1997) calls open-class repair initiators; they are ‘open’ in that they don’t specify the problem, and usually are done with ‘huh?’, and ‘what?’.

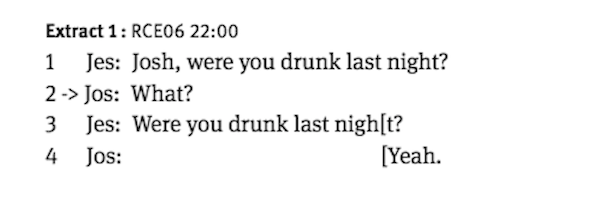

In Extract 1 above (from Kendrick, 2015) Jess treats Josh’s repair initiator ‘what?’ as not having heard (or paid attention), as she simply repeats the question.

In Extract 3 (from Kendrick, 2015), Jamie’s repair initiator “huh?” (line 7) raises a problem with the prior turn, but does not specify what the problem is. Max hedges his bets in the next turn, not only repeating the prior question “Are you playing?”, which addresses the issue of Jamie not having heard him, but also adds “footy” to clarify what the question refers to. There’s evidence that the repair is successful: Jamie is able to provide the answer (line 9) following Max’s repair/repeat of the question (line 8).

Not only is ‘huh?’ a frequently used repair initiator, it may well be universal in human communication! (Listen to ‘huh?’ in different languages, from Professor Nick Enfield’s research.)

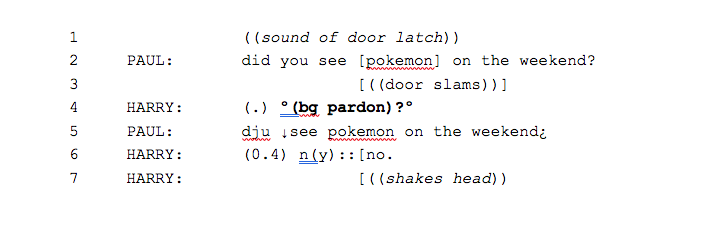

“Huh?” is often treated as a request to repeat, that the hearer didn’t actually hear what was said. The problem of mishearing can also be repaired with the initiators ‘pardon?’ or ‘sorry?’. Play the audio for the example below (from Church, Paatsch & Toe, 2017), and you can hear that Paul’s question (line 2) is hard to hear with the background noise.

Recipients can also highlight the problematic part of the prior turn. In the following example (Kendrick, 2015), the recipient identifies the part of the prior turn that is the troublesource:

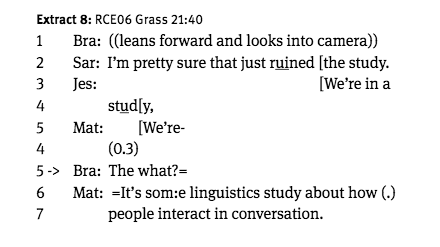

In line 2, we can see that the end of Sara’s turn is overlapped by Jess joining in the narrative about being in a linguistics study. Brack actually specifies the bit of the prior talk that is problematic, asking to specify the object: the what? Matt can tell what the trouble source is and does the repair by providing more context for the study.

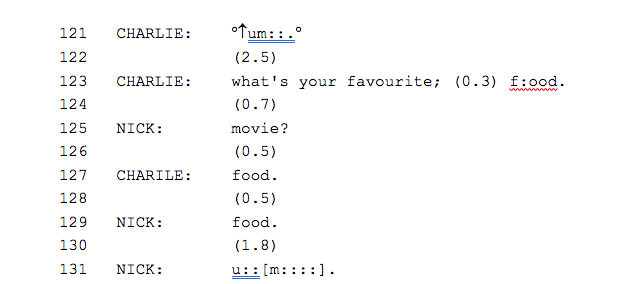

Recipients can also provide a candidate hearing of the prior utterance; that is, what they think they heard the other person say. In the example below (Church, Paatsch & Toe, 2017) Nick not only specifies the troublesource (the word in the prior turn he did not hear), but makes a suggestion/guess as to what the word (movie?) might be:

3.3 The preference for self-repair

As with all elements of the orderliness of talk-in-interaction, there are rules governing the use of repair. There is a preference in conversation for speakers to repair their own talk, ideally within their turn (self-initiated-self repair), or to provide a repair when queried by another (other-initiated self-repair). Least preferred, is for people to overtly correct another speaker (other-initiated other-repair).

In each of the examples above, the recipient initiates the repair, but leaves the speaker to do the repairing. In other words, other-initiated self-repair.

In other-initiated other-repair, the recipient not only identifies a problem, they fix the problem.

(This example appears as Figure 3 in Albert & de Ruiter, 2018)

This sort of explicit correction is not that common in conversation. Can you think why that would be? Consider the following example from Kendrick (2015):

There are any number of observations you might have made about this repair. Not only does the recipient (Jamie) not provide the speaker (Ben) with an opportunity to make the repair, she doesn’t even wait until the turn is finished. Jamie makes the repair so quickly it actually overlaps Ben’s turn. Is the repair necessary? No, because we can see that Jamie knows what diet Ben is referring to (it’s called the Butterfield diet).

Repair is used to maintain progressivity in interaction, something that needs to be done in order for the conversation to continue. But here, the other-initiated other-repair actually infringes of the progressivity of the talk: note the considerable pause - almost a full second - before Ben repeats the correction.

We can understand that the preference for self-repair facilitates face-saving, in that we give the speaker an opportunity to correct their own error before overtly pointing out and providing an explicit correction.

In the following example, from the Louis Theroux interview with Miriam Margoyles in the podcast Grounded, you’ll hear:

(1) an error that Louis does not repair (it’s clear what Miriam meant, and doesn’t need correction), and

(2) an error that he does repair (it’s clear what Miriam meant, but Louis decides does need correction).

Play the excerpt below to see if you can hear these two different types of other-initiated repair.

There’s a social cost to overtly correcting other people. Louis does not correct “sky” to “skype” but does initiate and make the repair when the distinction has more weight: it’s an important distinction between being treated like a child (infantalise), and killing a child (infanticide)!

How repair is managed has direct implications in clinical contexts, both in terms of confirming understanding and in the maintenance of the therapeutic relationship. For example, my notes on McCabe et al (2018):

Both self-repair and other-repair allow a greater shared understanding by providing mechanisms for locating and resolving potential trouble sources. It also demonstrates how the speaker is taking the listener’s perspective into account as it exposes the speaker’s efforts to resolve miscommunication and their commitment and engagement to the conversation. Thus McCabe et al. (2018) propose that the greater effort invested in repair, the better the patient feels during the interaction as the higher the quality and outcomes of the conversation, the greater the placebo effect produced by the psychiatrist-patient communication.

Let’s return to our example from a Cognitive Behavioral Therapy session, where the focus of discussion is the client’s dread of speaking in class. Here we see the therapist ask the client to rate her emotions on a scale of 1- 100:

(The full video extract is published on www.psychotherapy.net.)

In the example above, we see the preference for other-initiated self-repair in action. Rather than make a correction, the repair initiation is done by querying the number used, and in fact serves as an opportunity for the participants to display affiliation or mutual regard. This is a good example of regular, everyday, common-as-muck repair.

Self-repair provides us with some insight into the cognitive process of the speaker, an interactional phenomena that you are expert at tuning into in your work.

Other-initiated self-repair (huh? you what?) from the listener flags that there’s a problem of some sort, but allows the speaker to make the repair.

Other-initiated other repair is not common in everyday conversation, but is evident in therapy talk where the psychologist may overtly correct the speaker to illustrate a possibly flawed perception.

In fact, what the therapist does in every next turn makes relevant the work of therapy. Revisions of clients’ talk may not function simply as repair but serve to transpose understanding. There are two distinct (interactional) ways to re-frame the client’s talk: formulations and interpretations. We’ll look at each in detail in the next two modules of the course.

Summary

Repair is not only editing our speech as we go; it is the primary mechanism for resolving misunderstanding. The opportunity to clarify presents itself at each and every turn. The stunning efficiency of the turn-taking system for interaction is that we have an in-built apparatus for assuming that we make sense to others. We can manage intersubjectivity, on a turn-by-turn basis, and we assume that if no repair initiator is produced in the next turn, all is well.

The absence of repair does not mean that there is no misunderstanding - we can never be sure that others interpret as we intend. The fact that, if there is repair, repair is done immediately means that the other speaker always has the opportunity to clarify in the very next turn. For the most part a ‘now or never’ principle operates in conversation; we can return to a troublesource, but if we don’t do it right away, it takes a whole lot more interactional work.

Repair in psychotherapy teaches us much about claims to knowledge and how reported events are collaboratively constructed by therapist and client. Thinking about the content you’ve worked through in this section of the course, respond to the following reflection:

How does repair illuminate the client’s understanding of the problem at hand?

Further reading

References used throughout the course are available through the course homepage, but here’s a good summary paper on repair:

Albert, S. and de Ruiter, J.P. (2018). Repair: The interface between interaction and cognition. Topics in Cognitive Science, 10, 279-313. https://doi.org/10.1111/tops.12339

You can return to course homepage here, or to continue, simply click on ‘4. Formulations’ below right.