1. Turn taking

In this first section of the course we will come to understand the pervasive, systematic, orderly, and spectacularly efficient organisation of turns at talk in human interaction.

There are systematic rules that govern conversation. This is not theory, but empirical fact. The next video explains three key points: (1) where these rules come from, (2) why these rules are facts rather than theory of conversation, and (3) how these rules provide for efficiency in interaction. (And a body of evidence on the how of therapy talk.)

Here’s the example of Ivanka Trump flouting many rules of conversation. Watch the clip at least three times and see how many infringements you can spot!

What conversational rules did you notice Ivanka break?

Talk is ordered (so we know what to do when), talk is rule governed (so infractions such as talking when another person has not finished their turn can be heard as rude, inattentive, assertive etc.), and talk is sequential (so what comes next necessarily orients to what has just been said). These rules governing talk-in-interaction appear superficially simple, but in fact provide for an extraordinarily efficient machinery for social interaction. Let’s look at each of three key features of the rules of conversation: (1) one turn at a time; (2) speaker change occurs; and (3) one turn after another.

2.1 One turn at a time

Contributions to a conversation are built one turn at a time*. One speaker at a time promotes intelligibility of the turn – i.e. we can hear each other – and the opportunity for each speaker to display knowledge, stance, hesitation or any number of actions in their turn. We can see (hear) what’s going on and monitor the ongoing actions by virtue of this ‘one turn at a time’ rule.

Overlap and gaps between turns happen surprisingly infrequently. Speakers are so attuned to projecting the end of another speaker’s turn, that next turns overwhelming occur within 0.1 second of the prior turn completion.

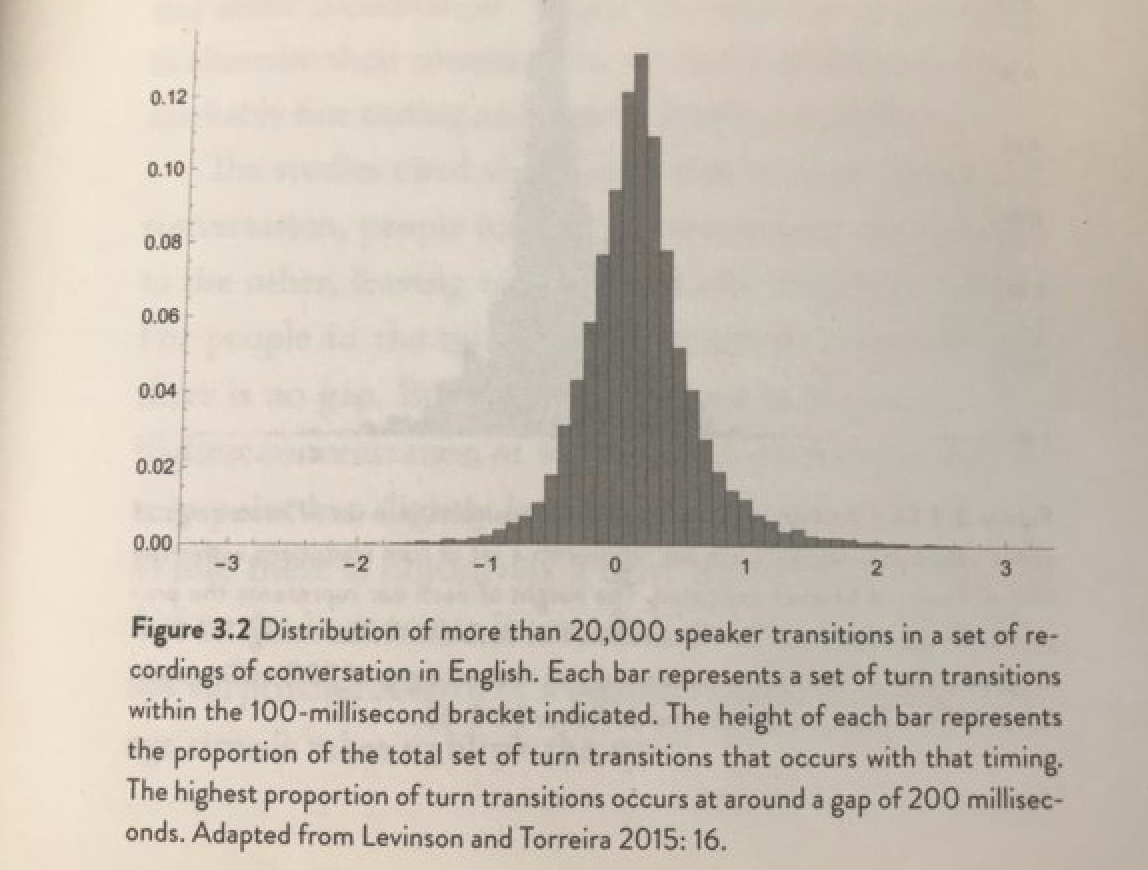

Evidence from Nick Enfield’s work shows us that in English, there is barely a perceptible gap between one speaker finishing and the next speaker starting.

Timing of turn transitions (Enfield, 2017, p. 39)

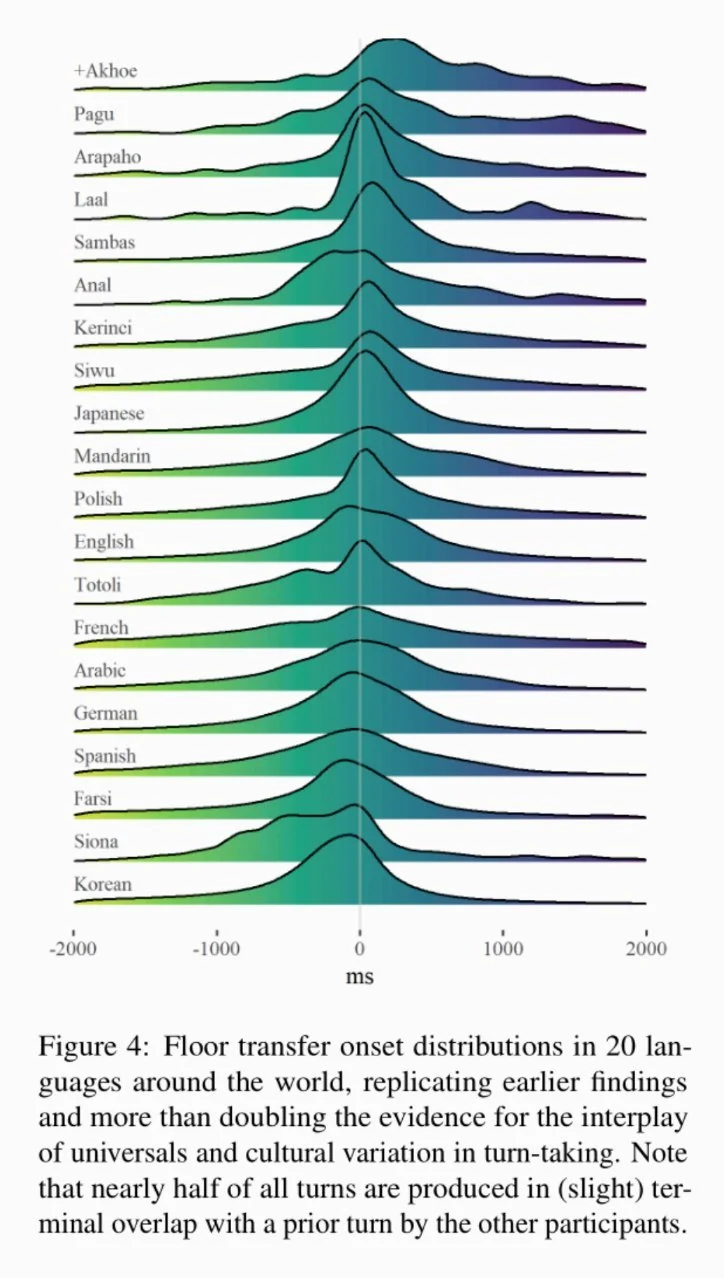

And it turns out, this is a universal human language phenomenon, as data from other languages show us similar accuracy of predicting when one turn finishes and the next can begin.

Figure posted by Mark Dingemanse @DingemanseMark

It’s not just that speakers are good at predicting or projecting the end of the other’s turn, we know how small the window is to be the next speaker, and draw on a range of resources to bid for the next turn.

We use our understanding of semantics (word meaning), syntax (the grammar of an utterance), prosody or intonation (eg rising at the end of a question), eye gaze (the speaker typically shifts gaze to another speaker just prior to the end of a turn) to pre-empt the end of the turn. We recognise the current speaker has not yet finished if the turn is semantically, syntactically, prosodically or pragmatically incomplete.

Importantly, where there is overlap, it most commonly occurs at a turn transition relevant place (ie. when the current speaker might conceivably be finished). The next speaker then repeats the part of their turn that was overlapped, and so it continues. How we manage overlapping talk is further evidence of the rule that there is only one speaker at a time.

Let’s look at (hear) how that happens in practice. To provide an example, here’s a clip from Louis Theroux’s podcast Grounded, recorded during lockdowns in the COVID-19 pandemic (interviews over zoom). It’s a short 3 minute clip from Louis’ interview with the actor and activist Miriam Margolyes. If you listen to the clip, we can then make some observations about how the talk is organised.

In the interview excerpt, we hear that both orient to the rule of one speaker at a time. Evidence for this claim is available where there is overlap: if a speaker begins when the other hasn’t actually finished, they stop, and wait for the next turn transition relevant place. Here’s an example:

You can see that in line 86 Louis begins to say something in response to Miriam’s declaration that she’s not gonna do [ironing]. Notably this occurs after a pause (half a second in line 85), so either speaker can select as next speaker. They both begin at the same time, but – orienting to the rule of one speaker at a time – Louis abandons his turn immediately as Miriam goes on to resist being asked to do ironing.

(If you’re interested in this point where one turn finishes and the next begins, Dr Emily Hofstetter has made an excellent video on turn constructional units (bits of talk or action – e.g. nodding – that make up a turn) and turn transition relevant places (points in the talk where another speaker may take a turn).

2.2. Speaker change occurs

Any speaker can self-select to be the next speaker, including the current speaker, and people use a range of practices to hold or bid for the floor.

In any everyday conversation – some professional contexts constrain who can talk, and when – the current speaker can select the next speaker (eg, “what do you think, Sue?”), the current speaker can choose to continue, or another speaker can self-select to take the next turn in the conversation.

For example, are there any particular speaker rights to the next turn following a sneeze? Watch this short clip from Seinfield.

As with anticipating the end of the turn, a self-selecting next speaker can draw on a range of resources to bid for the next turn. These include beginning just as the other speaker finishes a turn (ie to get in first) or using a range of embodied cues that they are self-selecting to be the next speaker: hand gesture; head tilt, audible in-breath, mouth opening. As speakers we are sensitive to these cues.

Even these pre-verbal toddlers have learnt a range of these cues:

Some funny anecdote about a missing sock? These children are pre-verbal but have already learnt many things about how conversation works.

By paying close attention to where and how speaker change occurs and recurs, we start to notice the very features of interaction that we use as speakers to monitor and maintain progressivity in interaction, i.e. things moving along smoothly.

Speaker rights may vary in different contexts; therapists, for example, may have rights to interrupt (i.e. intentional overlapping). The immediate context also determines the length and timing of turns; longer pauses, for example, are used in therapy for particular reasons. These context-specific practices, however, stem from the regular rules of regular conversation.

A third key feature of conversation is that turns at talk are produced one after another.

2.3. One turn after another

This fact of one-turn-after-another in conversation provides us with a ‘next-turn proof procedure: we can see in the recipient’s response just how s/he/they understood the prior turn’ (Sidnell, 2013, p. 79).

In other words, rather than guessing if we were understood, we can see how the other person understood us by what they do in the very next turn.

The one turn-after-another-ness of human interaction provides us with a spectacularly efficient mechanism for checking meaning as we go.

We see that there is a contiguity in conversation, such that each turn necessarily responds to the immediately prior turn. In other words:

“a turn-at-talk is contingent in some fashion on the other’s prior turn, and sets up contingencies of its own for what comes next, for how the recipient will respond (turns-at-talk are, as Heritage, 1984, p.242 puts it, “context shaped and context renewing”).”

This notion that turns at talk are context shaped (ie determined by the setting, participants and preceding talk) and context renewing (ie placing constraints on possible next actions) is helpful in deepening our understanding of therapy talk as a collaborative activity.

It is the ‘nextness’ of talk-in-interaction that allows us to see what has been understood by the immediately prior action.

In the excerpt from Louis’s interview with Miriam, we heard Louis make a metacommentary on Miriam’s mishearing of his question:

This few seconds of talk is remarkable in that we very rarely have to make this sort of explicit notation of the breakdown in intersubjectivity. Explaining the misunderstanding is a pretty cumbersome process – we’ll see in the next module how efficiently misunderstandings can be resolved due to the nextness of turns at talk – and Louis evidently treats the breakdown of alignment and affiliation as needing overt repair to get the interview back on track.

Ordinarily, displays of understanding produced in each next turn are sufficient to manage the progressivity of interaction. In collaboratively building intersubjectivity turn-by-turn, speakers use the inferences of the immediately prior action – ie. what was just said – and the subsequent, relevant next action (ie. what should come next). It is the ‘nextness’ of interaction that proves foundational to the interactional work of therapy, and the sequences of turns through which transformation is achieved.

The organisation of next turns at talk is the focus of the next module of our course.

Summary

In this first module we have learnt that conversation is structured and managed by speakers taking turns, at turn-transition relevant places (ie where the other speaker might have completed), one turn after another. Understanding these basic building blocks of conversation, allows us to see how these very same mechanisms are used in therapy talk.

These rules of conversation are pervasive: all talk is organised one speaker at a time, with changes of speaker, one turn after another. The systematic use of these rules is evident in the efficiency of managing turn-taking in conversation, and where the rules are borken (e.g. intentionally interrupting, or talking over somebody, is distinctly different from frequent but invariably brief overlap).

Thinking about the content you’ve worked through in this section of the course, respond to the following reflection:

How is an understanding of turn-taking rules useful for psychologists?

Further reading

References used throughout the course are available through the course homepage, but here’s the seminal paper on turn-taking:

You can return to the course homepage here, or continue by clicking on ‘Sequences of action’ below right.